The German unification and freedom movement (1800 - 1848)

The late 18th century saw the emergence throughout Europe of political movements dedicated to the pursuit of national unification on the basis of liberty. In Germany this development began relatively late. Political conditions in the Holy Roman Empire - known in Germany as the ‘Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation’ - were still entirely determined by the traditional structures of the authoritarian state that characterised the latter part of the age of absolutism. Although the Ancien Régime had been criticised from several quarters in the German territories, it took a long time for any recognisable signs to appear of developments that might seriously challenge the existing order.

Not until the Napoleonic conquests of the early 19th century was the old regime undermined and a comprehensive process of political modernisation set in motion. Reforms in the states of the French-occupied Confederation of the Rhine and a new awareness of the evident inferiority of the old order triggered reformist efforts in other German states, particularly in Prussia. At the same time, resistance against the French occupation contributed to the formation of a German nationalist movement, which not only sought the liberation of the French-occupied areas but also propagated demands for national unification and political self-determination.

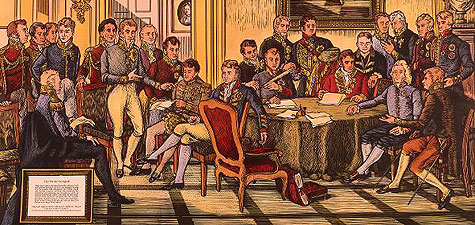

New political order established at the Congress of Vienna

After the victory over Napoleon, the Congress of Vienna met from September 1814 to June 1815 to redraw the political map of Europe. The negotiations were largely characterised by attempts to bring about the restoration of the pre-revolutionary order. While the aim in terms of foreign policy was to restore the balance of power among the states of Europe, the domestic aim was to re-establish the monarchic principle, preferably without concessions to liberal and democratic ideology. Instead of the nation state to which many people aspired, the German princes created the German Confederation, comprising 37 principalities and four free cities. The only federal body was the Confederate Assembly in Frankfurt am Main, over which Austria presided and which was later rechristened Deutscher Bundestag, or German Federal Diet. Although the German Confederation had limited scope for constructive action because of the cumbersome nature of its institutional structures, it proved to be an effective instrument for the suppression of opposition activists over a lengthy period.

The beginnings of parliamentary life in Germany

The Federal Act - the document establishing the German Confederation - prescribed the adoption of constitutions in the individual states, but the application of the relevant clause left much to be desired. While a number of central and northern German states eventually adopted constitutions, Prussia and Austria rejected the introduction of constitutions for their sovereign territories until 1848. Only in the states of southern Germany were constitutions adopted from the outset; these established a form of representation based on the estates of the realm and granted limited civil liberties and participatory rights. The representative assemblies that were created in this context gave the opposition movement new opportunities to shape developments and marked the start of the growth of parliamentary democracy in Germany. These assemblies, known as Landtage, generally comprised two chambers. The first chamber contained representatives of the ruling houses and the high nobility as well as dignitaries from politics, the church and society appointed by the monarch. The seats in the second chamber were assigned to particular social groups on the basis of fixed quotas, and the members representing these groups were often elected indirectly by means of a stratified class system of franchise. Although laws and tax-raising measures were subject to the approval of the Landtage, these assemblies had little scope for constructive action. Accordingly, in spite of some liberal reforms, substantive changes were invariably thwarted by the monarchs’ insistence on their right to act as sole representatives of the people.

Ferment and repression in the Vormärz period

Despite the restoration of the monarchic order, liberal and nationalist ideas were still being expounded, particularly among the bourgeoisie and at the universities. The Wartburg Festival of 18 October 1817, at which some 500 students gathered to voice their criticism of the status quo, was the first nationwide event held by the movement for national unification. The murder of a writer, August von Kotzebue, by Karl Ludwig Sand, a member of the liberal nationalist student fraternity known as the Burschenschaft, in Mannheim in 1819 heralded a phase of stricter surveillance and harsher repression. The Carlsbad Decrees, adopted in 1819 at the instigation of Austria’s foreign minister, Klemens von Metternich, established a police-state regime of surveillance and repression, designed to keep a tight lid on any opposition activity. As part of the so-called ‘demagogue prosecutions’ by the Central Investigation Commission which was set up in Mainz, draconian sanctions were used to silence leading representatives of the opposition. This was a severe blow to the organisation and development of the nationalist and liberal movement. Broad sections of the bourgeoisie who sympathised with the movement withdrew resignedly into the private idyll of the supposedly apolitical Biedermeier lifestyle.

The opposition movement received fresh stimulus from the July Revolution in Paris and the Polish Uprising at the start of the 1830s. Demonstrations and disturbances occurred in many places as people protested against unfair economic conditions and political repression. In Brunswick, Saxony, the Electorate of Hesse and Hanover, the ruling dynasties were compelled to make concessions on constitutions and civil rights. On the initiative of the Press and Fatherland Association, more than 20,000 people gathered at Hambach Castle on 27 May 1832 for a major national rally to demand the creation of a democratic German nation state in a free Europe. This first major mass political demonstration in Germany, at which many participants carried flags in black, red and gold - the colours of the Burschenschaft, which were generally recognised as a symbol of German unity - gave the opposition movement a huge boost. After that, the call for constitutional change could no longer be silenced.